|

|

@@ -0,0 +1,661 @@

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+# #ifdef PRIMER_BOOK

|

|

|

+===== Example of Classes for Geometric Objects =====

|

|

|

+# #else

|

|

|

+======= Inner Workings of the Pysketcher Tool =======

|

|

|

+# #endif

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+We shall now explain how we can, quite easily, realize software

|

|

|

+with the capabilities demonstrated above. Each object in the

|

|

|

+figure is represented as a class in a class hierarchy. Using

|

|

|

+inheritance, classes can inherit properties from parent classes

|

|

|

+and add new geometric features.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+# #ifndef PRIMER_BOOK

|

|

|

+===== Example of Classes for Geometric Objects =====

|

|

|

+# #endif

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+We introduce class `Shape` as superclass for all specialized objects

|

|

|

+in a figure. This class does not store any data, but provides a

|

|

|

+series of functions that add functionality to all the subclasses.

|

|

|

+This will be shown later.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+=== Simple Geometric Objects ===

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+One simple subclass is `Rectangle`:

|

|

|

+!bc pycod

|

|

|

+class Rectangle(Shape):

|

|

|

+ def __init__(self, lower_left_corner, width, height):

|

|

|

+ p = lower_left_corner # short form

|

|

|

+ x = [p[0], p[0] + width,

|

|

|

+ p[0] + width, p[0], p[0]]

|

|

|

+ y = [p[1], p[1], p[1] + height,

|

|

|

+ p[1] + height, p[1]]

|

|

|

+ self.shapes = {'rectangle': Curve(x,y)}

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+Any subclass of `Shape` will have a constructor which takes

|

|

|

+geometric information about the shape of the object and

|

|

|

+creates a dictionary `self.shapes` with the shape built of

|

|

|

+simpler shapes. The most fundamental shape is `Curve`, which is

|

|

|

+just a collection of $(x,y)$ coordinates in two arrays `x` and `y`.

|

|

|

+Drawing the `Curve` object is a matter of plotting `y` versus `x`.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+The `Rectangle` class illustrates how the constructor takes information

|

|

|

+about the lower left corner, the width and the height, and

|

|

|

+creates coordinate arrays `x` and `y` consisting of the four corners,

|

|

|

+plus the first one repeated such that plotting `x` and `y` will

|

|

|

+form a closed four-sided rectangle. This construction procedure

|

|

|

+demands that the rectangle will always be aligned with the $x$ and

|

|

|

+$y$ axis. However, we may easily rotate the rectangle about

|

|

|

+any point once the object is constructed.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+Class `Line` constitutes a similar example:

|

|

|

+!bc pycod

|

|

|

+class Line(Shape):

|

|

|

+ def __init__(self, start, end):

|

|

|

+ x = [start[0], end[0]]

|

|

|

+ y = [start[1], end[1]]

|

|

|

+ self.shapes = {'line': Curve(x, y)}

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+Here we only need two points, the start and end point on the line.

|

|

|

+However, we may add some useful functionality, e.g., the ability

|

|

|

+to give an $x$ coordinate and have the class calculate the

|

|

|

+corresponding $y$ coordinate:

|

|

|

+!bc pycod

|

|

|

+ def __call__(self, x):

|

|

|

+ """Given x, return y on the line."""

|

|

|

+ x, y = self.shapes['line'].x, self.shapes['line'].y

|

|

|

+ self.a = (y[1] - y[0])/(x[1] - x[0])

|

|

|

+ self.b = y[0] - self.a*x[0]

|

|

|

+ return self.a*x + self.b

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+Unfortunately, this is too simplistic because vertical lines cannot

|

|

|

+be handled (infinte `self.a`). The source code of `Line` therefore

|

|

|

+provides a more general solution at the cost of significantly

|

|

|

+longer code with more tests.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+A circle gives us somewhat increased complexity. Again we represent

|

|

|

+the geometic object by a `Curve` object, but this time the `Curve`

|

|

|

+object needs to store a large number of points on the curve such

|

|

|

+that a plotting program produces a visually smooth curve.

|

|

|

+The points on the circle must be calculated manually in the constructor

|

|

|

+of class `Circle`. The formulas for points $(x,y)$ on a curve with radius

|

|

|

+$R$ and center at $(x_0, y_0)$ are given by

|

|

|

+!bt

|

|

|

+\begin{align*}

|

|

|

+x &= x_0 + R\cos (t),\\

|

|

|

+y &= y_0 + R\sin (t),

|

|

|

+\end{align*}

|

|

|

+!et

|

|

|

+where $t\in [0, 2\pi]$. A discrete set of $t$ values in this

|

|

|

+interval gives the corresponding set of $(x,y)$ coordinates on

|

|

|

+the circle. The user must specify the resolution, i.e., the number

|

|

|

+of $t$ values, or equivalently, points on the circle. The circle's

|

|

|

+radius and center must of course also be specified.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+We can write the `Circle` class as

|

|

|

+!bc pycod

|

|

|

+class Circle(Shape):

|

|

|

+ def __init__(self, center, radius, resolution=180):

|

|

|

+ self.center, self.radius = center, radius

|

|

|

+ self.resolution = resolution

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+ t = linspace(0, 2*pi, resolution+1)

|

|

|

+ x0 = center[0]; y0 = center[1]

|

|

|

+ R = radius

|

|

|

+ x = x0 + R*cos(t)

|

|

|

+ y = y0 + R*sin(t)

|

|

|

+ self.shapes = {'circle': Curve(x, y)}

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+As in class `Line` we can offer the possibility to give an angle

|

|

|

+$\theta$ (equivalent to $t$ in the formulas above)

|

|

|

+and then get the corresponding $x$ and $y$ coordinates:

|

|

|

+!bc pycod

|

|

|

+ def __call__(self, theta):

|

|

|

+ """Return (x, y) point corresponding to angle theta."""

|

|

|

+ return self.center[0] + self.radius*cos(theta), \

|

|

|

+ self.center[1] + self.radius*sin(theta)

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+There is one flaw with this method: it yields illegal values after

|

|

|

+a translation, scaling, or rotation of the circle.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+A part of a circle, an arc, is a frequent geometric object when

|

|

|

+drawing mechanical systems. The arc is constructed much like

|

|

|

+a circle, but $t$ runs in $[\theta_0, \theta_1]$. Giving

|

|

|

+$\theta_1$ and $\theta_2$ the slightly more descriptive names

|

|

|

+`start_angle` and `arc_angle`, the code looks like this:

|

|

|

+!bc pycod

|

|

|

+class Arc(Shape):

|

|

|

+ def __init__(self, center, radius,

|

|

|

+ start_angle, arc_angle,

|

|

|

+ resolution=180):

|

|

|

+ self.center = center

|

|

|

+ self.radius = radius

|

|

|

+ self.start_angle = start_angle*pi/180 # radians

|

|

|

+ self.arc_angle = arc_angle*pi/180

|

|

|

+ self.resolution = resolution

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+ t = linspace(self.start_angle,

|

|

|

+ self.start_angle + self.arc_angle,

|

|

|

+ resolution+1)

|

|

|

+ x0 = center[0]; y0 = center[1]

|

|

|

+ R = radius

|

|

|

+ x = x0 + R*cos(t)

|

|

|

+ y = y0 + R*sin(t)

|

|

|

+ self.shapes = {'arc': Curve(x, y)}

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+Having the `Arc` class, a `Circle` can alternatively befined as

|

|

|

+a subclass specializing the arc to a circle:

|

|

|

+!bc pycod

|

|

|

+class Circle(Arc):

|

|

|

+ def __init__(self, center, radius, resolution=180):

|

|

|

+ Arc.__init__(self, center, radius, 0, 360, resolution)

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+A wall is about drawing a curve, displacing the curve vertically by

|

|

|

+some thickness, and then filling the space between the curves

|

|

|

+by some pattern. The input is the `x` and `y` coordinate arrays

|

|

|

+of the curve and a thickness parameter. The computed coordinates

|

|

|

+will be a polygon: going along the originally curve and then back again

|

|

|

+along the vertically displaced curve. The relevant code becomes

|

|

|

+!bc pycod

|

|

|

+class CurveWall(Shape):

|

|

|

+ def __init__(self, x, y, thickness):

|

|

|

+ # User's curve

|

|

|

+ x1 = asarray(x, float)

|

|

|

+ y1 = asarray(y, float)

|

|

|

+ # Displaced curve (according to thickness)

|

|

|

+ x2 = x1

|

|

|

+ y2 = y1 + thickness

|

|

|

+ # Combine x1,y1 with x2,y2 reversed

|

|

|

+ from numpy import concatenate

|

|

|

+ x = concatenate((x1, x2[-1::-1]))

|

|

|

+ y = concatenate((y1, y2[-1::-1]))

|

|

|

+ wall = Curve(x, y)

|

|

|

+ wall.set_filled_curves(color='white', pattern='/')

|

|

|

+ self.shapes = {'wall': wall}

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+=== Class Curve ===

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+Class `Curve` sits on the coordinates to be drawn, but how is

|

|

|

+that done? The constructor just stores the coordinates, while

|

|

|

+a method `draw` sends the coordinates to the plotting program

|

|

|

+to make a graph.

|

|

|

+Or more precisely, to avoid a lot of (e.g.) Matplotlib-specific

|

|

|

+plotting commands we have created a small layer with a

|

|

|

+simple programming interface to plotting programs. This makes it

|

|

|

+straightforward to change from Matplotlib to another plotting

|

|

|

+program. The programming interface is represented by the `drawing_tool`

|

|

|

+object and has a few functions:

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+ * `plot_curve` for sending a curve in terms of $x$ and $y$ coordinates

|

|

|

+ to the plotting program,

|

|

|

+ * `set_coordinate_system` for specifying the graphics area,

|

|

|

+ * `erase` for deleting all elements of the graph,

|

|

|

+ * `set_grid` for turning on a grid (convenient while constructing the plot),

|

|

|

+ * `set_instruction_file` for creating a separate file with all

|

|

|

+ plotting commands (Matplotlib commands in our case),

|

|

|

+ * a series of `set_X` functions where `X` is some property like

|

|

|

+ `linecolor`, `linestyle`, `linewidth`, `filled_curves`.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+This is basically all we need to communicate to a plotting program.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+Any class in the `Shape` hierarchy inherits `set_X` functions for

|

|

|

+setting properties of curves. This information is propagated to

|

|

|

+all other shape objects that make up the figure. Class

|

|

|

+`Curve` stores the line properties together with the coordinates

|

|

|

+of its curve and propagates this information to the plotting program.

|

|

|

+When saying `vehicle.set_linewidth(10)`, all objects that make

|

|

|

+up the `vehicle` object will get a `set_linewidth(10)` call,

|

|

|

+but only the `Curve` object at the end of the chain will actually

|

|

|

+store the information and send it to the plotting program.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+A rough sketch of class `Curve` reads

|

|

|

+!bc pycod

|

|

|

+class Curve(Shape):

|

|

|

+ """General curve as a sequence of (x,y) coordintes."""

|

|

|

+ def __init__(self, x, y):

|

|

|

+ self.x = asarray(x, dtype=float)

|

|

|

+ self.y = asarray(y, dtype=float)

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+ self.linestyle = None

|

|

|

+ self.linewidth = None

|

|

|

+ self.linecolor = None

|

|

|

+ self.fillcolor = None

|

|

|

+ self.fillpattern = None

|

|

|

+ self.arrow = None

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+ def draw(self):

|

|

|

+ drawing_tool.plot_curve(

|

|

|

+ self.x, self.y,

|

|

|

+ self.linestyle, self.linewidth, self.linecolor,

|

|

|

+ self.arrow, self.fillcolor, self.fillpattern)

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+ def set_linewidth(self, width):

|

|

|

+ self.linewidth = width

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+ det set_linestyle(self, style):

|

|

|

+ self.linestyle = style

|

|

|

+ ...

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+=== Compound Geometric Objects ===

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+The simple classes `Line`, `Arc`, and `Circle` could define the geometric

|

|

|

+shape through just one `Curve` object. More complicated figure elements

|

|

|

+are built from instances of various subclasses of `Shape`. Classes used

|

|

|

+for professional drawings soon get quite complex in composition and

|

|

|

+have a lot of geometric details, so here we prefer to make a very simple

|

|

|

+composition: the already drawy vehicle from

|

|

|

+Figure refref{sketcher:fig:vehicle0}.

|

|

|

+That is, instead of composing the drawing in a Python code we make a class

|

|

|

+`Vehicle0` for doing the same thing, and derive it from `Shape`.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+The `Shape` hierarchy is found in the `pysketcher` package, so to use these

|

|

|

+classes or derive a new one, we need to import `pysketcher`. The constructor

|

|

|

+of clas `Vehicle0` performs approximately the same statements as

|

|

|

+in the example program we developed for making the drawing in

|

|

|

+Figure refref{sketcher:fig:vehicle0}.

|

|

|

+!bc pycod

|

|

|

+class Vehicle0(Shape):

|

|

|

+ def __init__(self, w_1, R, L, H):

|

|

|

+ wheel1 = Circle(center=(w_1, R), radius=R)

|

|

|

+ wheel2 = wheel1.copy()

|

|

|

+ wheel2.translate((L,0))

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+ under = Rectangle(lower_left_corner=(w_1-2*R, 2*R),

|

|

|

+ width=2*R + L + 2*R, height=H)

|

|

|

+ over = Rectangle(lower_left_corner=(w_1, 2*R + H),

|

|

|

+ width=2.5*R, height=1.25*H)

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+ wheels = Composition(

|

|

|

+ {'wheel1': wheel1, 'wheel2': wheel2})

|

|

|

+ body = Composition(

|

|

|

+ {'under': under, 'over': over})

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+ vehicle = Composition({'wheels': wheels, 'body': body})

|

|

|

+ xmax = w_1 + 2*L + 3*R

|

|

|

+ ground = Wall(x=[R, xmax], y=[0, 0], thickness=-0.3*R)

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+ self.shapes = {'vehicle': vehicle, 'ground': ground}

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+Any subclass of `Shape` *must* define the `shapes` attribute, otherwise

|

|

|

+the inherited `draw` method (and a lot of other methods too) will

|

|

|

+not work.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+The painting of the vehicle could be offered by a method:

|

|

|

+!bc pycod

|

|

|

+ def colorful(self):

|

|

|

+ wheels = self.shapes['vehicle']['wheels']

|

|

|

+ wheels.set_filled_curves('blue')

|

|

|

+ wheels.set_linewidth(6)

|

|

|

+ wheels.set_linecolor('black')

|

|

|

+ under = self.shapes['vehicle']['body']['under']

|

|

|

+ under.set_filled_curves('red')

|

|

|

+ over = self.shapes['vehicle']['body']['over']

|

|

|

+ over.set_filled_curves(pattern='/')

|

|

|

+ over.set_linewidth(14)

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+The usage of the class is simple: after having set up an appropriate

|

|

|

+coordinate system a s previously shown, we can do

|

|

|

+!bc pycod

|

|

|

+vehicle = Vehicle0(w_1, R, L, H)

|

|

|

+vehicle.draw()

|

|

|

+drawing_tool.display()

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+The color from Figure ref{sketcher:fig:vehicle0:v2} is realized by

|

|

|

+!bc pycod

|

|

|

+drawing_tool.erase()

|

|

|

+vehicle.colorful()

|

|

|

+vehicle.draw()

|

|

|

+drawing_tool.display()

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+A complete code defining and using class `Vehicle0` is found in the file

|

|

|

+# #ifdef PRIMER_BOOK

|

|

|

+`vehicle2.py`.

|

|

|

+# #else

|

|

|

+"`vehicle2.py`": "http://hplgit.github.com/pysketcher/doc/src/sketcher/src-sketcher/vehicle2.py".

|

|

|

+# #endif

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+The `pysketcher` package contains a wide range of classes for various

|

|

|

+geometrical objects, particularly those that are frequently used in

|

|

|

+drawings of mechanical systems.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+======= Adding Functionality via Recursion =======

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+The really powerful feature of our class hierarchy is that we can add

|

|

|

+much functionality to the superclass `Shape` and to the "bottom" classe

|

|

|

+`Curve`, and all other classes for all types of geometrical shapes

|

|

|

+immediately get the new functionality. To explain the idea we first have

|

|

|

+to look at the `draw` method, which all classes in the `Shape`

|

|

|

+hierarchy must have. The inner workings of the `draw` method explain

|

|

|

+the secrets of how a series of other useful operations on figures

|

|

|

+can be implemented.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+=== Basic Principles of Recursion ===

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+We work with two types of class hierarchies: one Python class hierarcy,

|

|

|

+with `Shape` as superclass, and one *object hierarchy* of figure elements

|

|

|

+in a specific figure. A subclass of `Shape` stres its figure in the

|

|

|

+`self.shapes` dictionary. This dictionary represents the object hierarchy

|

|

|

+of figure elements for that class. We want to make one `draw` call

|

|

|

+for an instance, say our class `Vehicle0`, and then we want this call

|

|

|

+to be propagated to *all* objects that are contained in

|

|

|

+`self.shapes` and all is nested subdictionaries. How is this done?

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+The natural starting point is to call `draw` for each `Shape` object

|

|

|

+in the `self.shapes` dictionary:

|

|

|

+!bc pycod

|

|

|

+def draw(self):

|

|

|

+ for shape in self.shapes:

|

|

|

+ self.shapes[shape].draw()

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+This general method can be provided by class `Shape` and inherited in

|

|

|

+subclasses like `Vehicle0`. Let `v` be a `Vehicle0` instance.

|

|

|

+Seemingly, a call `v.draw()` just calls

|

|

|

+!bc pydoc

|

|

|

+v.shapes['vehicle'].draw()

|

|

|

+v.shapes['ground'].draw()

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+However, in the former call we call the `draw` method of a `Composition` object

|

|

|

+whose `self.shapes` attributed has two elements: `wheels` and `body`.

|

|

|

+Since class `Composition` inherits the same `draw` method, this method will

|

|

|

+run through `self.shapes` and call `wheels.draw()` and `body.draw()`.

|

|

|

+Now, the `wheels` object is also a `Composition` with the same `draw`

|

|

|

+method, which will run through the `shapes` dictionary, now containing

|

|

|

+the `wheel1` and and `wheel2` objects. The `wheel1` object is a `Circle`,

|

|

|

+so calling `wheel1.draw()` calls the `draw` method in class `Circle`,

|

|

|

+but this is the same `draw` method as shown above. This method will

|

|

|

+therefore traverse the circle's `shapes` dictionary, which we have seen

|

|

|

+consists of one `Curve` element.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+The `Curve` object holds the coordinates to be plotted so here `draw`

|

|

|

+really needs to do something "physical", namely send the coordinates to

|

|

|

+the plotting program. The `draw` method is outlined in the short listing

|

|

|

+of class `Curve` shown previously.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+We can go to any of the other shape objects that appear in the figure

|

|

|

+hierarchy and follow their `draw` calls in the similar way. Every time,

|

|

|

+a `draw` call will invoke a new `draw` call, until we eventually hit

|

|

|

+a `Curve` object in the "botton" of the figure hiearchy, and then that part

|

|

|

+of the figure is really plotted (or more precisesly, the coordinates

|

|

|

+are sent to a plotting programm).

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+When a method calls itself, such as `draw` does, the calls are known as

|

|

|

+*recursive* and the programming principle is referred to as

|

|

|

+*recursion*. This technique is very often used to traverse hierarchical

|

|

|

+structures like the figure structures we work with here. Even though the

|

|

|

+hierarchy of objects building up a figure are of different types, they

|

|

|

+all inherit the same `draw` method and therefore exhibit the same

|

|

|

+behavior with respect to drawing. Only the `Curve` object has a different

|

|

|

+`draw` method, which does not lead to more recursion. Without this

|

|

|

+different `draw` method in class `Curve`, the repeated `draw` calls would

|

|

|

+go on forever.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+=== Explaining Recursion ===

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+Understanding recursion is usually a challenge. To get a better idea of

|

|

|

+how recursion works, we have equipped class `Shape` with a method `recurse`

|

|

|

+which just visits all the objects in the `shapes` dictionary and prints

|

|

|

+out a message for each object.

|

|

|

+This feature allows us to trace the execution and see exactly where

|

|

|

+we are in the hierarchy and which objects that are visited.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+The `recurse` method is very similar to `draw`:

|

|

|

+!bc pydoc

|

|

|

+ def recurse(self, name, indent=0):

|

|

|

+ # print message where we are (name is where we come from)

|

|

|

+ for shape in self.shapes:

|

|

|

+ # print message about which object to visit

|

|

|

+ self.shapes[shape].recurse(indent+2, shape)

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+The `indent` parameter governs how much the message from this

|

|

|

+`recurse` method is intended. We increase `indent` by 2 for every level

|

|

|

+in the hierarchy. This makes it easy to see on the printout how far

|

|

|

+down in the hierarchy we are.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+A typical message written by `recurse` when `name` is `body` and

|

|

|

+the `shapes` dictionary contains two entries, `over` and `under`,

|

|

|

+will be

|

|

|

+!bc dat

|

|

|

+ Composition: body.shapes has entries 'over', 'under'

|

|

|

+ call body.shapes["over"].recurse("over", 6)

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+The number of leading blanks on each line corresponds to the value of

|

|

|

+`indent`. The code printing out such messages looks like

|

|

|

+!bc pycod

|

|

|

+ def recurse(self, name, indent=0):

|

|

|

+ space = ' '*indent

|

|

|

+ print space, '%s: %s.shapes has entries' % \

|

|

|

+ (self.__class__.__name__, name), \

|

|

|

+ str(list(self.shapes.keys()))[1:-1]

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+ for shape in self.shapes:

|

|

|

+ print space,

|

|

|

+ print 'call %s.shapes["%s"].recurse("%s", %d)' % \

|

|

|

+ (name, shape, shape, indent+2)

|

|

|

+ self.shapes[shape].recurse(shape, indent+2)

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+Let us follow a `v.recurse('vehicle')` call in detail, `v` being

|

|

|

+a `Vehicle0` instance. Before looking into the output from `recurse`,

|

|

|

+let us get an overfiew of the figure hierarchy in the `v` object

|

|

|

+(as produced by `print v`)

|

|

|

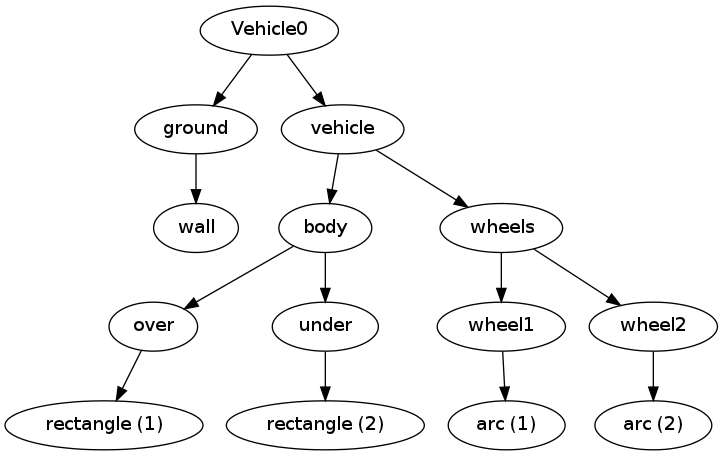

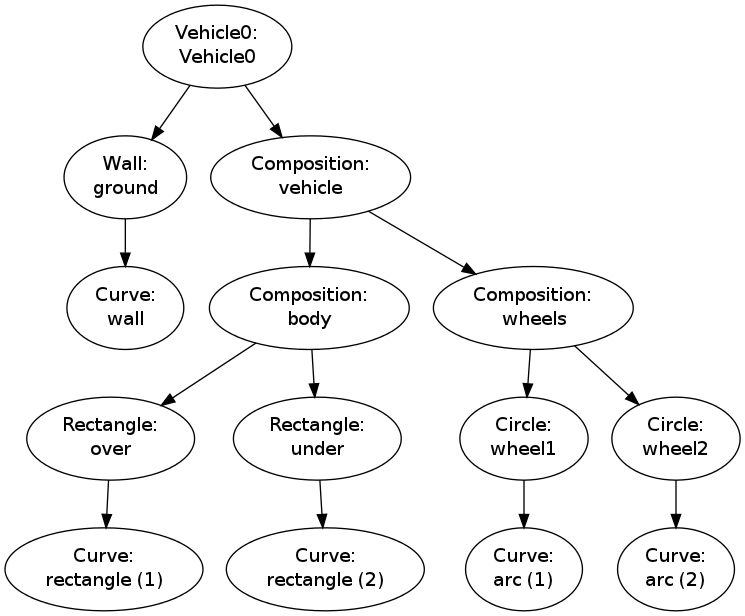

+!bc dat

|

|

|

+ground

|

|

|

+ wall

|

|

|

+vehicle

|

|

|

+ body

|

|

|

+ over

|

|

|

+ rectangle

|

|

|

+ under

|

|

|

+ rectangle

|

|

|

+ wheels

|

|

|

+ wheel1

|

|

|

+ arc

|

|

|

+ wheel2

|

|

|

+ arc

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+The `recurse` method performs the same kind of traversal of the

|

|

|

+hierarchy, but writes out and explains a lot more.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+The data structure represented by `v.shapes` is known as a *tree*.

|

|

|

+As in physical trees, there is a *root*, here the `v.shapes`

|

|

|

+dictionary. A graphical illustration of the tree (upside down) is

|

|

|

+shown in Figure ref{sketcher:fig:Vehicle0:hier2}.

|

|

|

+From the root there are one or more branches, here two:

|

|

|

+`ground` and `vehicle`. Following the `vehicle` branch, it has two new

|

|

|

+branches, `body` and `wheels`. Relationships as in family trees

|

|

|

+are often used to describe the relations in object trees too: we say

|

|

|

+that `vehicle` is the parent of `body` and that `body` is a child of

|

|

|

+`vehicle`. The term *node* is also often used to describe an element

|

|

|

+in a tree. A node may have several other nodes as *descendants*.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+FIGURE: [figs-sketcher/Vehicle0_hier2.png, width=600] Hierarchy of figure elements in an instance of class `Vehicle0`. label{sketcher:fig:Vehicle0:hier2}

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+Recursion is the principal programming technique to traverse tree structures.

|

|

|

+Any object in the tree can be viewed as a root of a subtree. For

|

|

|

+example, `wheels` is the root of a subtree that branches into

|

|

|

+`wheel1` and `wheel2`. So when processing an object in the tree,

|

|

|

+we imagine we process the root and then recurse into a subtree, but the

|

|

|

+first object we recurse into can be viewed as the root of the subtree, so the

|

|

|

+processing procedure of the parent object can be repeated.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+A recommended next step is to simulate the `recurse` method by hand and

|

|

|

+carefully check that what happens in the visits to `recurse` is

|

|

|

+consistent with the output listed below. Although tedious, this is

|

|

|

+a major exercise that guaranteed will help to demystify recrusion.

|

|

|

+Also remember that it requires some efforts to understand recursion.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+A part of the printout of `v.recurse('vehicle')` looks like

|

|

|

+!bc dat

|

|

|

+ Vehicle0: vehicle.shapes has entries 'ground', 'vehicle'

|

|

|

+ call vehicle.shapes["ground"].recurse("ground", 2)

|

|

|

+ Wall: ground.shapes has entries 'wall'

|

|

|

+ call ground.shapes["wall"].recurse("wall", 4)

|

|

|

+ reached "bottom" object Curve

|

|

|

+ call vehicle.shapes["vehicle"].recurse("vehicle", 2)

|

|

|

+ Composition: vehicle.shapes has entries 'body', 'wheels'

|

|

|

+ call vehicle.shapes["body"].recurse("body", 4)

|

|

|

+ Composition: body.shapes has entries 'over', 'under'

|

|

|

+ call body.shapes["over"].recurse("over", 6)

|

|

|

+ Rectangle: over.shapes has entries 'rectangle'

|

|

|

+ call over.shapes["rectangle"].recurse("rectangle", 8)

|

|

|

+ reached "bottom" object Curve

|

|

|

+ call body.shapes["under"].recurse("under", 6)

|

|

|

+ Rectangle: under.shapes has entries 'rectangle'

|

|

|

+ call under.shapes["rectangle"].recurse("rectangle", 8)

|

|

|

+ reached "bottom" object Curve

|

|

|

+...

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+This example should clearly demonstrate the principle that we

|

|

|

+can start at any object in the tree and do a recursive set

|

|

|

+of calls with that object as root.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+===== Scaling, Translating, and Rotating a Figure =====

|

|

|

+label{sketcher:scaling}

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+With recursion, as explained in the previous section, we can within

|

|

|

+minutes equip *all* classes in the `Shape` hierarchy, both present and

|

|

|

+future ones, with the ability to scale the figure, translate it,

|

|

|

+or rotate it. This added functionality requires only a few lines

|

|

|

+of code.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+=== Scaling ===

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+We start with the simplest of the three geometric transformations,

|

|

|

+namely scaling.

|

|

|

+For a `Curve` instance containing a set of $n$ coordinates

|

|

|

+$(x_i,y_i)$ that make up a curve, scaling by

|

|

|

+a factor $a$ means that we multiply all the $x$ and $y$ coordinates

|

|

|

+by $a$:

|

|

|

+!bt

|

|

|

+\[

|

|

|

+x_i \leftarrow ax_i,\quad y_i\leftarrow ay_i,

|

|

|

+\quad i=0,\ldots,n-1\thinspace .

|

|

|

+\]

|

|

|

+!et

|

|

|

+Here we apply the arrow as an assignment operator.

|

|

|

+The corresponding Python implementation in

|

|

|

+class `Curve` reads

|

|

|

+!bc cod

|

|

|

+class Curve:

|

|

|

+ ...

|

|

|

+ def scale(self, factor):

|

|

|

+ self.x = factor*self.x

|

|

|

+ self.y = factor*self.y

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+Note here that `self.x` and `self.y` are Numerical Python arrays,

|

|

|

+so that multiplication by a scalar number `factor` is

|

|

|

+a vectorized operation.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+An even more efficient implementation is

|

|

|

+to make use of in-place multiplication in the arrays, as this saves the creation

|

|

|

+of temporary arrays like `factor*self.x`, which is then assigned to

|

|

|

+`self.x`:

|

|

|

+!bc cod

|

|

|

+class Curve:

|

|

|

+ ...

|

|

|

+ def scale(self, factor):

|

|

|

+ self.x *= factor

|

|

|

+ self.y *= factor

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+In an instance of a subclass of `Shape`,

|

|

|

+the meaning of a method `scale` is

|

|

|

+to run through all objects in the dictionary `shapes` and ask

|

|

|

+each object to scale itself. This is the same delegation of actions

|

|

|

+to subclass instances as we do in the `draw` (or `recurse`) method. All

|

|

|

+all objects, except `Curve` instances, can share the same

|

|

|

+implementation of the `scale` method. Therefore, we place

|

|

|

+the `scale` method in the superclass `Shape` such that all

|

|

|

+subclasses inherit the method.

|

|

|

+Since `scale` and `draw` are so similar,

|

|

|

+we can easily implement the `scale` method in class `Shape` by

|

|

|

+copying and editing the `draw` method:

|

|

|

+!bc cod

|

|

|

+class Shape:

|

|

|

+ ...

|

|

|

+ def scale(self, factor):

|

|

|

+ for shape in self.shapes:

|

|

|

+ self.shapes[shape].scale(factor)

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+This is all we have to do in order to equip all subclasses of

|

|

|

+`Shape` with scaling functionality!

|

|

|

+Any piece of the figure will scale itself, in the same manner

|

|

|

+as it can draw itself.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+=== Translation ===

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+A set of coordinates $(x_i, y_i)$ can be translated $v_0$ units in

|

|

|

+the $x$ direction and $v_1$ units in the $y$ direction using the formulas

|

|

|

+!bt

|

|

|

+\begin{equation*}

|

|

|

+x_i\leftarrow x_i+v_0,\quad y_i\leftarrow y_i+v_1,\quad i=0,\ldots,n-1\thinspace . \end{equation*}

|

|

|

+!et

|

|

|

+The natural specification of the translation is in terms of a

|

|

|

+vector $v=(v_0,v_1)$.

|

|

|

+The corresponding Python implementation in class `Curve` becomes

|

|

|

+!bc cod

|

|

|

+class Curve:

|

|

|

+ ...

|

|

|

+ def translate(self, v):

|

|

|

+ self.x += v[0]

|

|

|

+ self.y += v[1]

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+The translation operation for a shape object is very similar to the

|

|

|

+scaling and drawing operations. This means that we can implement a

|

|

|

+common method `translate` in the superclass `Shape`. The code

|

|

|

+is parallel to the `scale` method:

|

|

|

+!bc cod

|

|

|

+class Shape:

|

|

|

+ ....

|

|

|

+ def translate(self, v):

|

|

|

+ for shape in self.shapes:

|

|

|

+ self.shapes[shape].translate(v)

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+=== Rotation ===

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+Rotating a figure is more complicated than scaling and translating.

|

|

|

+A counter clockwise rotation of $\theta$ degrees for a set of

|

|

|

+coordinates $(x_i,y_i)$ is given by

|

|

|

+!bt

|

|

|

+\begin{align*}

|

|

|

+ \bar x_i &\leftarrow x_i\cos\theta - y_i\sin\theta,\\

|

|

|

+ \bar y_i &\leftarrow x_i\sin\theta + y_i\cos\theta\thinspace .

|

|

|

+\end{align*}

|

|

|

+!et

|

|

|

+This rotation is performed around the origin. If we want the figure

|

|

|

+to be rotated with respect to a general point $(x,y)$, we need to

|

|

|

+extend the formulas above:

|

|

|

+!bt

|

|

|

+\begin{align*}

|

|

|

+ \bar x_i &\leftarrow x + (x_i -x)\cos\theta - (y_i -y)\sin\theta,\\

|

|

|

+ \bar y_i &\leftarrow y + (x_i -x)\sin\theta + (y_i -y)\cos\theta\thinspace .

|

|

|

+\end{align*}

|

|

|

+!et

|

|

|

+The Python implementation in class `Curve`, assuming that $\theta$

|

|

|

+is given in degrees and not in radians, becomes

|

|

|

+!bc cod

|

|

|

+ def rotate(self, angle, center):

|

|

|

+ angle = radians(angle)

|

|

|

+ x, y = center

|

|

|

+ c = cos(angle); s = sin(angle)

|

|

|

+ xnew = x + (self.x - x)*c - (self.y - y)*s

|

|

|

+ ynew = y + (self.x - x)*s + (self.y - y)*c

|

|

|

+ self.x = xnew

|

|

|

+ self.y = ynew

|

|

|

+!ec

|

|

|

+The `rotate` method in class `Shape` is identical to the

|

|

|

+`draw`, `scale`, and `translate` methods except that we

|

|

|

+recurse into `self.rotate(angle, center)`.

|

|

|

+

|

|

|

+We have already seen the `rotate` method in action when animating the

|

|

|

+rolling wheel at the end of Section ref{sketcher:vehicle1:anim}.

|